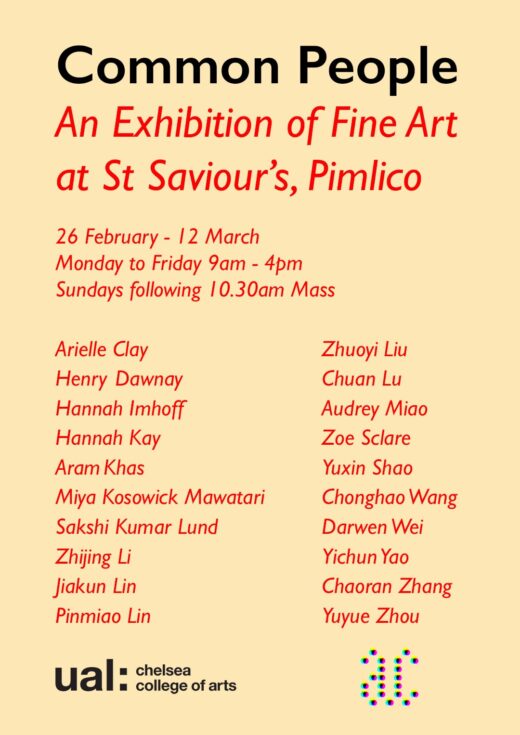

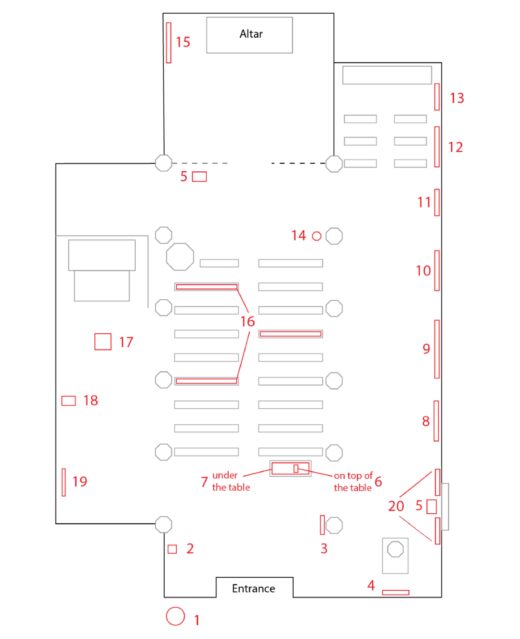

Common People

Common People is the third exhibition organised by Arts Chaplaincy Projects at St Saviour’s, Pimlico, with this year’s show including work by artists who are members of the congregation as well as those studying on the MA Fine Art Programme at UAL Chelsea College of Arts. The developing relationship between the college and the church is reflected in the exhibition’s title, which also refers to the Common Worship → liturgy that informs the daily life of the church, as well as Pulp’s Brit-pop anthem → about a relationship between ‘home’ and international art students.

With thanks to the artists, Fr Matthew and everyone at St Saviour’s Church, Ian Monroe and colleagues at Chelsea College of Arts, and special thanks to Duncan Wooldridge and colleagues at UAL Camberwell Photographic Resource Centre.

1. Chonghao Wang

‘Leakage’

metal, sugar

Like Asakusa (a Japanese process of making sculptures out of sugar), I have used coloured icing sugar to simulate the glass of a church window and set these ‘glasses’ on a shelf made of metal, with springs at the joints between the icing sugar and the metal, with the sculpture placed in the outdoor space of the church to cast an enchanting light and shadow in the sun. As the temperature and humidity change, the icing will melt, just like the leaves falling.

2. Zoe Sclare

‘A Guide to Being a Jewish Woman’

limited edition zine (available from Village)

A project exploring ideas of modesty and beauty within the orthodox Jewish community, this publication is also a visual representation of the artist’s experience of being a Jewish woman, showing a surreal and almost humorous side to Judaism, whilst including such serious topics as antisemitism (as seen in the screenshot of an offensive text sent to the artist). Zoey’s images have been produced following interviews she conducted with a variety of Jewish women.

zoeyjacqueline.com

@7oeyjacqueline

3. Zhijing Li

‘Ruler Cross’

folding carpenter rulers, fixing brackets

The combined length of the rulers approximates the distance from the entrance of the church to the altar.

4. Yuxin Shao

‘First’

oil on canvas

My works have always started from myself, discussing the relationship between with the world and myself, focusing on the taboos under human moral sense. To break the bounaries you have drawn for yourself and experience the immensity that you are. The aim is to unshackle yourself from the limited identity you have forged as a result of your own ignorance, and live the initial way the Creator made you.

syx56780.wixsite.com/my-site-1

@hivaleria0508

5. Yuyue Zhou

‘Peace in and out / Welcome’

polypropylene, rubber, spray paint

Welcome: “Our aspirations to upward are in one way or another the same.”

Peace in and out: “The carpet of the Peace of Entry and Exit is a traditional Chinese family-based religious object”

6. Chuan Lu

‘CLEAN’

digital print on 350gsm card

People sacrifice a lot to make everyday things work. I pay a lot of attention to the people behind the scenes in my work, and the contrast they present after that. What I am trying to say here is the resemblance I feel in a church. People come in and pray and go, the only thing that remains stable and unshakable is Jesus himself.

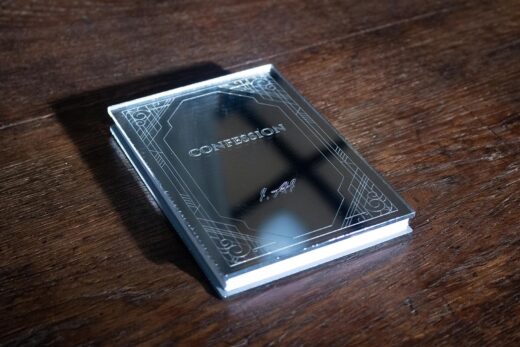

7. Yichun Yao

‘I, AI’

3 videos, table, LED screens, headphones, mirror reflection book

Humans make mistakes all the time, but we never stopped creating. Technology is one of our creations. I created this art work to show how AI made confessions to human for their mistakes, challenges and moral defect. The confessions were generated by AI robots themselves, and I use artificial voice to read these texts.

Yao Yichun is an artist exploring and experiencing human emotions, perceptions, relationships, trust and control in the virtual high-tech environment, experiencing and questioning what effects could AI, algorithm, big data, internet bring to our emotions and relationships. Yao likes to use different mediums, as well as herself to examine all the questions. Yao works with installation, performance, sound, video, texts, photography, apps and internet.

8. Hannah Kay

‘Love is my Religion’

mixed media, photography

The Care Bear here is the bear of love, set inside a romanticised scene characterising comfort and care. I want the bear to highlight a childlike nostalgia and initial joy, although this also speaks of the consumerist world we live in and how we all so often feel that by purchasing goods we will feel happy or become more easily loveable.

hannahkaybutcher.wixsite.com/site

@hannahkaycreative

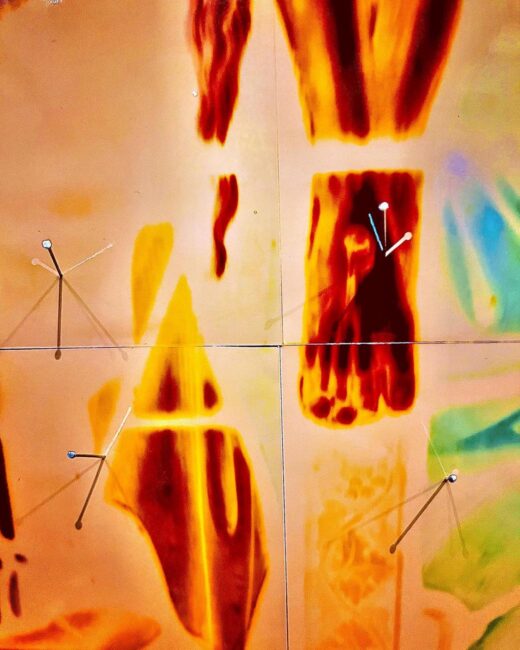

9. Aram Khas

‘Stained Glass #1’, ‘Stained Glass #2’

unique c-type colour photographic paper

I have used the interior of the church as a photographic enlarger to form an image on colour photographic paper inside a pinhole camera (camera obscura) by means of natural light through stained glass. While it was not until the 19th century that images could be fixed on light sensitive material, it is believed that the camera obsura has been used for religious and artistic purposes from prehistoric times.

10. Pinmiao Lin

‘Moving’

acrylic, bible

It is written in the Bible: ‘Go to the ant, you lazybones; consider its ways, and be wise’. Proverbs 6

When I was a child, I would always observe the ants in groups carrying food that was larger than themselves. At that time I understood the old Chinese saying, ‘The many pick up the fire’ which is the meaning of solidarity.

linpinmiao77.wixsite.com/miaooo

@liinpinmiao_

11. Zhuoyi Liu

‘Merge’

wool felt, plastic

To emphasise the communication and intersection of the bible and the world, I wanted to combine elements of the church with everyday objects, changing the colours, materials, shapes and patterns of the original objects, so that the biblical world is reflected in reality.

liuzhuoyilzy.wixsite.com/liuzhuoyi

@zhuoyi1011

12. Henry Dawnay

‘Thor, from Darkness to Light: Thor’s Ghost, The Fisher King, Cosmic Soup’

acrylic on canvas

henrydawnay.com

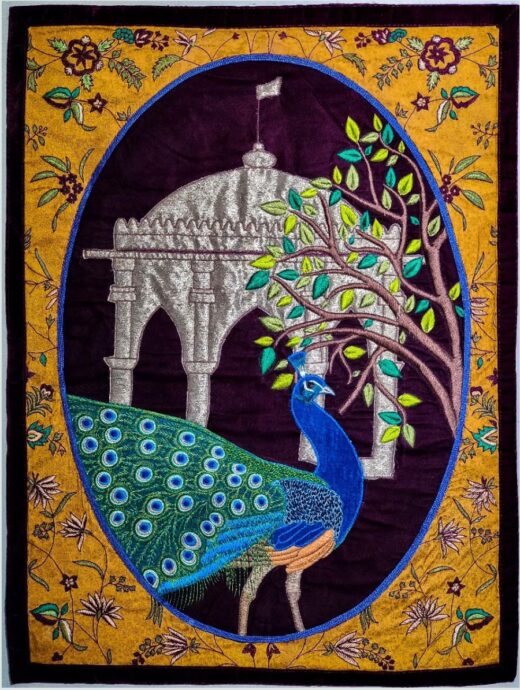

13. Sakshi Kumar Lund

‘مور’

hand embroidery on Pakistani textiles

I always feel a sense of comfort when I look at a peacock. Since childhood I frequently visited Narayan Mandir, a temple in my hometown Karachi. Inside the temple are several peacocks that always fascinate me because of their beauty. I often associate the bird peacock with that temple; hence, I always feel comforted when I look at them. It reminds me of the peace and calm I experienced in that temple. A church is also a place that makes you feel closer to God and provides comfort. Hence, I want to bring those memories to another place of worship.

14. Miya Kosowick Mawatari

‘Yumedono’

concrete, incense

Every morning one senko incense will burn inside a compact octogonal open structure made of cement. The structure is a maquette referencing the Buddhist monument Yumedono in Horyu-ji, Ikagara, Nara Prefecture. Yumedono otherwise known as Hallway of Dreams is one of the oldest surviving wooden Buddhist temples in the world (8th Century). It is currently a UNESCO heritage site. Recently, the ancient building was referenced in Kengo Kuma’s 2019 observation deck in Japan (article with more info here). The reason for Yumedono’s octogonal shape remains a mystery. I have early memories of visiting these monuments with my mother and brother as a way to connect us to our heritage. My memories of the space feel fragmented, but the smell of the wood and senko incense remain distinct.

miyakosowickmawatari.cargo.site

@miyakmawatari

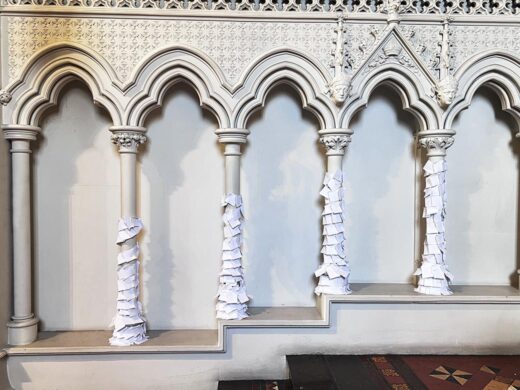

15. Chaoran Zhang

‘Time Change’

paper, acrylic line, adhesive

Time is a concept that is both important and not easily noticed, like these load-bearing pillars or corners. So I wanted to express the change of time by stacking paper on the wall or pillar, presenting the visual effect of the crumbling fragments and artificial repair that we observe when time is constantly destroyed. Because when the object is wrapped by many papers of the same color, it feels like the object is peeling off, revealing a sense of time like the annual rings of a tree. In this way, I want to use a corner of the church to express the traces of time produced by the walls or columns by pasting neatly the paper, some of which peel off to represent the passage of time, which will give the audience an intuitive sense of the building’s history.

chaoran.art

@supernature.zcr

16. Jiakun Lin

‘Wisdom’

adhesive vinyl, dimensions variable

‘…and wisdom to know the difference’ is a sentence from a prayer that everyone can relate to no matter if one is religious or not.

17. Audrey Miao

‘Their Voices’

brass, pearl, beads, CZ stone

I wanted to visualize the recorded voices of my pets, making them into jewellery, so they can be carried around without causing additional burden. Sounds are invisible and only exist for a while; I want my pets to be with me all the time, even if I can’t keep them with me all the time. I think church is a place where people can pray, confess, and make all people feel that ‘all things are equal’. People always regard animals as inferior, so I’d like to bring them into the church and give them a place of their own.

audreymmyue.wixsite.com/my-site

18. Darwin Wei

Untitled

wood, acrylic, mirror, LED tape

weiyuanfeng.com

@darwin_yuanfeng

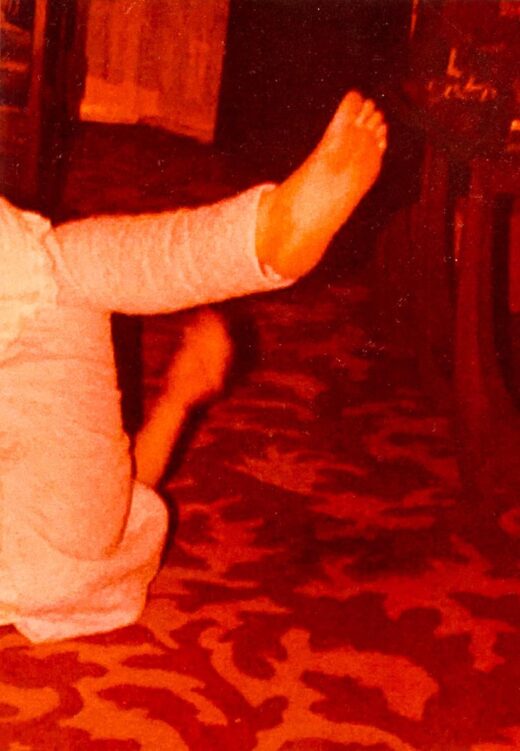

19. Hannah Imhoff

‘Peace be with you’

video documentation of performance (camera: Monika Drabot)

During the mass I loved the “salutation”, where everybody looked in each others eyes, raised their hand in greeting and wished each other “peace be with you”. This moment of looking so clear and directly in foreign eyes and shaking other people’s hands was quite special for me, so I wondered if one could bring this out in our daily life. I thought about an intervention in the public transport, in a bus or a tube. I thought about this place, because here people come on a daily basis together but refuse to admit each others presence.

hannahimhoff.com

@imhoff_hannah

20. Arielle Clay

Untitled

oil on canvas and silk paper

21. Yuying Huang

‘Pixel Christ’

performance during exhibition opening event

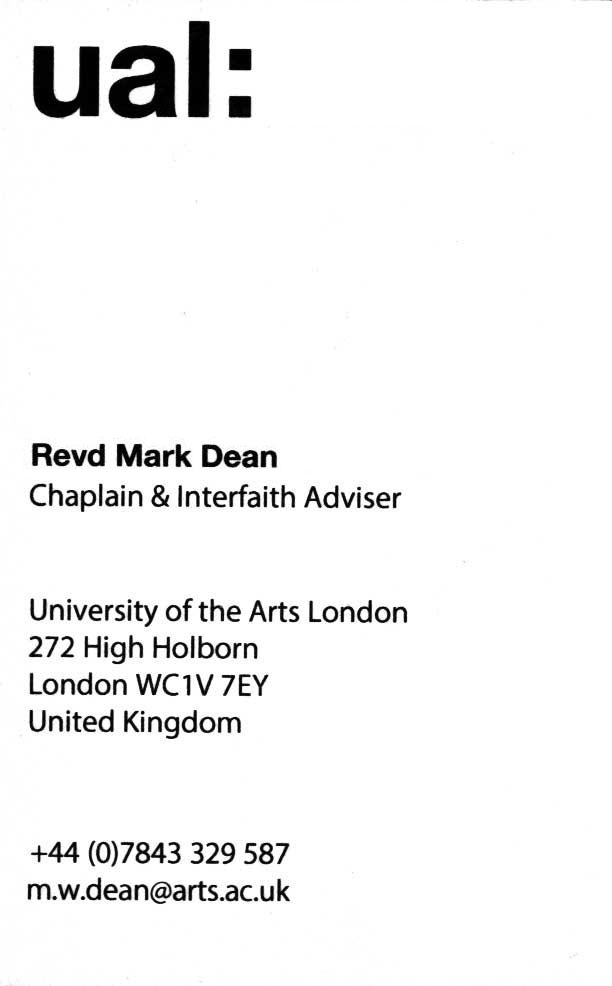

Sermon preached by Revd Mark Dean on the occasion of the opening of the exhibition.

We are now in the season of Lent, the forty day period that precedes Holy Week, when Jesus’ earthly life was brought to an end by his crucifixion on Good Friday. But Lent is also associated with the forty days that Jesus spent in the wilderness before beginning his ministry, hence the gospel reading appointed for today, the first Sunday of Lent.

But the first day of Lent was on Wednesday, when some of you will have been in this church to receive on your forehead the mark of the cross in the ashes of repentance. I myself received this ash from the hand of Fr Matthew on Thursday, when I was here as coordinator of Arts Chaplaincy Projects, to help install the exhibition Common People that you can see around you.

Does it matter that I kept the tradition on Thursday, and not Wednesday? In the Eastern Orthodox church, the beginning of Lent is not Ash Wednesday, but Clean Monday. And while in both traditions, Lent precedes the same festival of Easter, that too is often kept on different days, because the Eastern and Western churches use different astronomical calendars to calculate the date of Easter each year. So perhaps the question is not so much when one keeps a particular day of remembrance, but whether one remembers to do so at all; in which case, the purpose of assigning a particular day in the calendar is not to ensure astronomical alignment, but in order that people can gather together in community — as a common people.

It may seem strange to talk about commonality, when our focus today is on an individual in the wilderness, in this case Jesus; but we can all find ourselves alone in what may feel like a spiritual wilderness at times, and certainly we all experience temptation. However, unlike Jesus, we are all sinners. We can argue about what constitutes sin, and what the consequences of this might be, but all Christians must surely agree with the statement itself; indeed, as we have just heard St Paul say in his letter to the Romans: ‘death came through sin, and so death spread to all, because all have sinned’. And while Jesus alone did not sin, by his temptation in the wilderness he was providing a model for all of us who do. So what might we learn from his example here?

In our world, the temptation to sin is usually spoken of in terms of sex, or maybe chocolate. But the temptation of Christ did not involve either of these. Jesus was not tempted with a fantasy of sex, but the reality of power. Indeed, in Luke’s account of the Temptation, the devil says to him, ‘To you I will give the glory and authority of all the kingdoms of the world, for it has been given over to me, and I give it to anyone I please.’ And we might do well to remember this statement of the devil, anytime we find ourselves in positions of authority in the world, or desirous of power.

Jesus was offered power – the power to produce bread where there was none, the power to save the fallen, and ultimately the power to be High King. But of course, he already had these powers, as would soon be demonstrated by the feeding of the five thousand, the healing miracles, and ultimately in the Resurrection, when Jesus conquered death, our greatest enemy.

So the devil was tempting Jesus not with a fantasy, of what he was not, but a reality, of what he already was, or at least could be, if he allowed it. So why did Jesus refuse what was already his? The problem was the source, the channel, the name in which he would have these things. ‘All these I will give you’, said the devil, ‘if you will fall down and worship me.’ But Jesus refused to do so, and so refused to accept the power of the world, instead emptying himself of the power he already had. He denied himself, and took up his cross.

Later in Matthew’s gospel, we read that Jesus told his disciples, ‘If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it. For what will it profit them if they gain the whole world but forfeit their life?’

What might it mean, to deny ourselves in this way? When Jesus modelled self-denial, he resisted the power of the world. In his case, power was offered personally, but for most of us, the power of the world is manifest through institutions; for example, universities, where at graduation ceremonies the presiding officer will say something like ‘by the authority vested in me, I confer these degrees on these candidates’.

University degrees are awarded in different classes, or not at all in the case of students judged to have failed. But many universities have begun to recognise that their exercise of this power of judgement can be affected by factors other than the academic. UAL, where I serve as chaplain, has stated that ‘radical change is needed to dismantle systemic racism within our university and the creative industries.’ Similarly, the Church of England, which ordained me as a priest, and has sent me to serve at UAL, has been described by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, as ‘deeply institutionally racist’.

This does not necessarily mean that individuals within these institutions are purposefully racist, although of course they may be. But it does mean that the systems that have disadvantaged or excluded people on the basis of race have at the same time advantaged others — especially those in positions of authority. Thus, it could be said that for these institutions to actively commit to changing these systems is a kind of denying of self; in this case, the self of white supremacy.

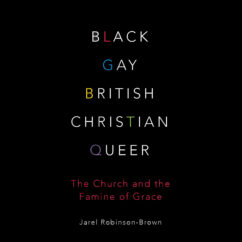

One might hope that something equivalent could be said in terms of sexuality, and in the case of the university I’m glad to say it can; UAL has an active policy of LGBTQ+ inclusion. Unfortunately, the Church of England is not only institutionally heterosexist, in not allowing marriage between same sex couples, it is in some quarters actively homophobic, via a strident insistence that homosexuality is a sin.

I mentioned before that the world’s understanding of temptation is primarily in terms of sex, and chocolate. And so it is a curious thing that the church’s opposition to gay sex, which is mentioned in the Bible about as often as chocolate, is often justified on the grounds that the church does not follow the ways of the world; however, it would seem that this is exactly what it is doing. For the church to be truly countercultural, it might let go of its obsession with sex, and turn instead to a subject that is indeed insisted upon in the Bible; that is, love, expressed as justice and mercy.

In saying this, I am aware that there are some who will say that it is those like me, who argue for LGBTQ+ inclusion, who are the strident ones. Why am I talking about sex here, when I could be talking about art, for example? My answer is that I am not interested in speaking of art as separate from life; that is why I value this current exhibition so much, because it involves art and artists in the life of the church. But some of these artists would be excluded from full participation in the life of the Church of England, on the basis of who and how they love.

In arguing for LGBTQ+ inclusion I am primarily concerned with those who are currently excluded, but I also believe that diversity in the church is for the good of all. It is hard to love those who say that I and my friends are going to hell. However, I love the Anglican Communion, not just despite those I disagree with, but because of them. I love this diversity because I believe that it reflects something of the breadth of the love of God for all people, and because it is only in such diversity that I feel that there can be a place for me, as an individual.

Nonetheless, there are powerful voices within the church which maintain that it is not possible to maintain unity in such diversity, and that those who argue for inclusion are excluding themselves from communion with the church, and therefore from the grace of God. Well so be it. If it comes to that, I will have to stand with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who said “I would refuse to go to a homophobic heaven. No, I would say sorry, I mean I would much rather go to the other place. I would not worship a God who is homophobic and that is how deeply I feel about this. I am as passionate about this campaign as I ever was about apartheid. For me, it is at the same level.” (And let’s not forget that many passages of scripture were invoked in defence of apartheid, as they were to justify the slavery and colonialism that preceded it.)

But what of art? What might it mean for an artist to deny themselves? And what cross are we to take up? I once asked the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, a question along these lines, and he said that that the first thing would be for artists to lose their messiah complex — and, he added, certain sections of the church might do likewise. We are called to take up our own crosses, not those of others. Jesus has already died to save us all, once and for all. And having done so, he rose again, and sent us the gifts of his Holy Spirit.

So if we follow Christ, we will not deny our human nature, nor our creative gifts, but rather we will use these, not to increase our individual power and status, but as an offering, in service to the world and those who we share it with; and thereby in the service of God, who created the world and whose people dwell in common therein.