The Spiritual Exercises is an online exhibition mediating memory and longing via the parameters of the present.

There was a moment, corresponding to but not defined by the lockdown. Some artists were locked out of their studios, and others, who maybe don’t have studios, but situate their practice in the outside world, were locked in. In this regard, they were like many other workers; but there is a sense in which ‘working from home’ can mean something different for artists. In this moment also, perhaps for the first time ever, the air in the city was clean, and as a result everything looked different, especially in the seemingly endless sunshine. The architectural detail of each building we passed during our daily exercises was made visible, and found to be extraordinary. And there was another curious aspect to this moment; we were collectively living in a way that at least intended to put the needs of the most vulnerable first. It didn’t last long — the air is thickening, and our social spirit is running thin again — but we paused for a moment; and perhaps we will remember what this felt like, when we come to make decisions about the next right thing to do in our ongoing crisis, which began long before the current pandemic, and is environmental, social, and indeed spiritual.

It was during this moment that The Spiritual Exercises project took place, and around a hundred artists responded to an open call prompted by the following texts:

When I was ill recently (with symptoms of the novel coronavirus) I found myself travelling in my mind to places in my past. The memories were vivid, and sustained. It was a bit like they say happens before you die; your life flashing before you, but in this case it was more like slow motion. And of course I wasn’t dying, thank God, although I wasn’t so sure about that at the time…

Whatever the cause, it seemed to help, this journeying in my mind; and although it was spontaneous, once I was there I could decide where to go next. For example, one of the places I found myself in was the house where I lived as a teenager. I could walk from room to room, open the front door, and go out into the street. I could then retrace my old routes, like the walk along the river I took every day with my dog. There was a timber yard there (long gone, sadly) where coasters would sail from the Baltic Sea. I found I could remember details of these ships: the red livery, and names like Ida Bres and Astrid Bres. When I began to recover, I started searching online and found archive images of some of these vessels, taken in the place where I had just been walking in my memory.

Perhaps one of the reasons I started visualising places from the past so vividly was the deep desire to be somewhere else; somewhere away from the fear of illness, and also away from the constraints of lockdown. And maybe it is natural to want to go back, to go ‘home’, at such times — although the irony is that the time and place I was recalling was not exactly safe, and neither was I really free. Nevertheless, the desire to return to a supposed Golden Age, an Eden, is a common one, and has long been associated with both art and spirituality. (Mark Dean)

In speaking of this desire for our own far-off country, which we find in ourselves even now, I feel a certain shyness. I am almost committing an indecency. I am trying to rip open the inconsolable secret in each one of you — the secret which hurts so much that you take your revenge on it by calling it names like ‘nostalgia’ and ‘Romanticism’ and ‘adolescence’; the secret also which pierces with such sweetness that when, in very intimate conversation, the mention of it becomes imminent, we grow awkward and affect to laugh at ourselves; the secret we cannot hide and cannot tell, though we desire to do both. We cannot tell it because it is a desire for something that has never actually appeared in our experience. We cannot hide it because our experience is constantly suggesting it, and we betray ourselves like lovers at the mention of a name. Our commonest expedient is to call it beauty and behave as if that had settled the matter. Wordsworth’s expedient was to identify it with certain moments in his own past. But all this is a cheat. If Wordsworth had gone back to those moments in the past, he would not have found the thing itself, but only the reminder of it; what he remembered would turn out to be itself a remembering. The books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them; it was not in them, it only came through them, and what came through them was longing. These things — the beauty, the memory of our own past — are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself they turn into dumb idols, breaking the hearts of their worshippers. For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited. (C.S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory)

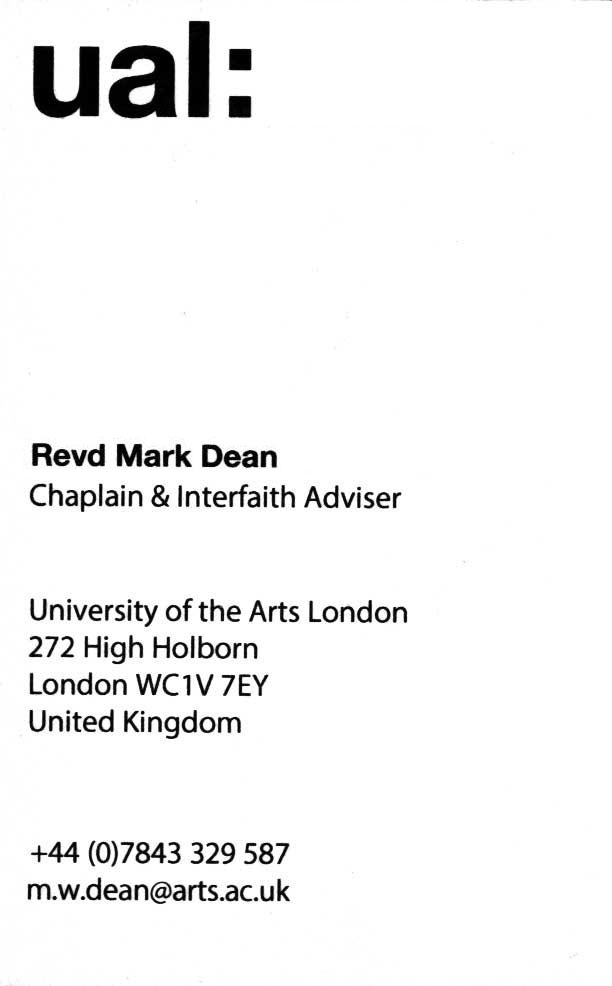

© 2020 Arts Chaplaincy Projects

All rights reserved by the artists

For further information on individual artists, please follow the links on their pages

For further information regarding this project, please contact Mark Dean (details below)